By Joel Pablo Salud

However much I disagree with the way Sultan Jamalul Kiram III and his royal forces conducted their entry into Sabah, I can’t help but honor the courage displayed by the Tausugs. Theirs is a warrior society undiminished by time. For him and his lineage, Sabah was not a piece of land to claim. It was theirs for the longest time, every bit of soil and shrub of that patch of the former North Borneo. It was not simply some real estate under the Kiram name. History had attested that North Borneo was and is still Sulu Sultanate territory, the one roaring reality that had stood unchanged amid the yellowing of years and varying voices claiming the Sulu throne.

As fierce battle raged between the Kirams and Malaysian forces in Lahad Datu all the way to adjacent villages, it bears mentioning that another battle was taking place in cyberspace. News reports maintained that hackers from Malaysia and the Philippines conducted a salvo of attacks against each other to mirror the fracas on land. Even as the seven battalions of Malaysia’s armies swooped down on the brave 300 Tausugs holed up in one Sabah town, hackers from Anonymous allegedly raised a campaign against each other in retaliation for hostilities. From reality to virtual reality, it seems the relationship between the Philippines and Malaysia will never be the same again.

The war in cyberspace was inexorable. The day and age of a totally different contest for power had begun. Without guns and the thunder of a million soldiers’ footsteps, “wars” can now be waged with the flick of an “enter” button. I will not hazard to say it’s an exciting prospect in light of death tolls nations incur in real-time skirmishes. As information slowly equals the worth of actual human lives, losses in cyber wars could be as equally devastating as conventional warfare.

Speaking of conventional warfare, Malaysia seemed to have missed the point of this engagement entirely. The Tausugs of Sulu had kept watch over their territories and people for centuries, the cost of which didn’t come easy. The battles they had fought—from the time the Sultan of Brunei begged for their help to quell a rebellion, to the day when the Tausug rebel Kimar Tulawie fought the forces of Martial Law under Gen. Mayo, to the very hour the Kirams now face the overwhelming forces of Malaysia—has kept the valiant Tausugs in tiptop form. They fought sword-in-hand with Spain as a superpower to another superpower until the conquistadores thought it was a bad idea to begin with. Sulu had lost sons and husbands, fathers, mothers and daughters. Tausugs have been known to brandish not only sword but women warriors as well. In this part of the Southeast, Muslim and Christian Tausugs fought bravely to stand on what they think is theirs to own. They have kept their honor intact through the centuries until the hour a ruse was staged by the British Crown and Malaysia and foretold the Sultanate’s slow yet inevitable fall.

If only Malaysia had taken this bit of history seriously, it would not have suffered the losses it had incurred in Lahad Datu. I sympathize with Malaysian families who now endure the pain of loss because of this armed engagement in Sabah. They have only their government to blame for it.

As in any war the battle for hearts and minds is inevitable. News items showing varying persuasions and arguments littered Facebook’s newsfeed at the very start of the armed engagement. It’s befuddling to read foreign press taking up the Malaysian spiel. The New York Times took the events to mean that a “religious army” had entered Sabah. This simple yet serious gaffe in research forces the ball to fall into a different court. Then the UK Guardian came with its headline: “Malaysia bombs Borneo to expel squatter sultan’s private army” with the subhead, “Deadly escalation in crisis sparked by Filipino clan sneaking into Sabah state and asserting ancestral ownership rights.”

Squatters? Sneaking into Sabah? Watering the issue down to a “Filipino clan asserting its rights” over a disputed ancestral area helps little in discovering what had really transpired. I totally disagree with the notion of some that history can hardly be used as a basis for facts, in light of its ever evolving nature. If that is the case, then what the hell are we avid disciples of history for? Yes, there’s a solid trail to all this, however convoluted it may seem. One has but to dig deeper not only into the cache of papers but attitudes accepted in that old world order. And mind you, that old world order cannot be understood in its full context outside of the way people of ancient kingdoms understood and accepted their condition at the time.

Let’s take for example this argument: that Sabah’s thoughts should’ve been considered on the issue of its transfer from the Sultanate of Brunei to the Sultanate of Sulu. The idea wishes to elevate the old North Borneo to the position largely held by modern states today, where it must have a voice in the matter of nationality. It’s as if the theorist is arguing from the premise that North Borneo was a thriving state outside the kingdom of Brunei and the Sulu archipelago at the time. That premise cannot hold water any more than Malaysia’s hands can cup the Tausug warriors.

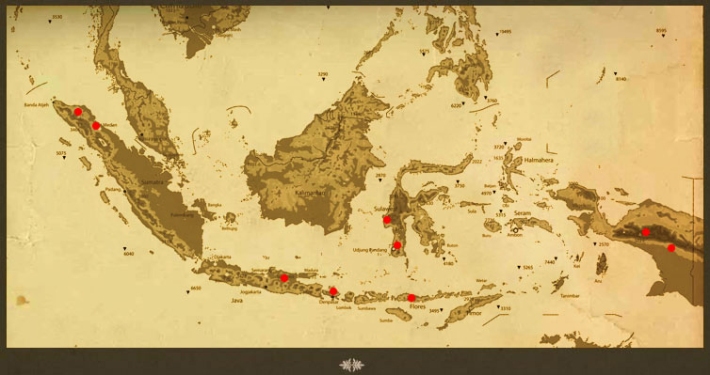

Why? Granted the North Borneo may seem an independent state from a modern perspective, geographical lines didn’t exist then as we know these lines to exist today. Jovito Salonga, in his 1963 debacle with Sen. Sumulong on the issue of the Sabah claim, asserted that no such demarcations existed. Experts have tracked land bridges connecting the Sulu archipelago with North Borneo, connecting the archipelagic empire in one seamless whole. In the minds of the royals and Sulu’s inhabitants, North Borneo was much a part of the Sulu archipelago as Palawan is to the Philippines. That mindset exists well up to modern times; which is why Suluks have been coming in and out of North Borneo since the glory days of the Sultans. I won’t even be surprised if Brunei’s reasons for the transfer of Sabah to Sulu’s hands had been based, among others, to this fact. North Borneo was a destination the Suluks had always considered home.

On the line of reasoning that Sabahans suffered estrangement because its voice wasn’t in any way heard during the transfer from Brunei to Sulu, I have only this to offer as a thought bubble: Wouldn’t it be more precise to say that such estrangement or alienation “felt” by, say Sabahans, is merely conjecture? A way of modern interpretation of what may have been left unsaid in all this? We have the benefit of hindsight and modern studies, thank God for that. But we all have yet to read a document saying that the Sabahans of old refused to be a part of the Sultanate of Sulu at the time it was handed over by the Sultan of Brunei. Sulu being what it was before, rich in ways we can only imagine, the population of North Borneo then may have wanted it more than anything else.

Another argument I read, which compared our own historical engagement with Spain, didn’t exactly coincide with Sabah’s experience. It assumed that the old North Borneo had always been a separate political and geographic entity, which by and large was in the rightful position to claim self-determination. It therefore hints that North Borneo should have been consulted during the transfer from Brunei to Sulu. But history had nothing to say about that theory. More to the point, modern historians (or so this one claims to be) cannot make conclusions about the ancient world using modern parameters for analysis. Again let me reiterate: that old world order cannot be understood in its full context outside of the way people of ancient kingdoms understood and accepted their condition at the time.

History has this to say: much of the Philippine archipelago then was conquered territory, invaded by a malignant power outside its own. Sulu archipelago remained free despite attempts by Spain to subdue its borders. Sabah has been part of a reigning kingdom long before the various sultanates existed. Called the Nusantara, this archipelagic empire was part of the Buddhist-Hindu Majapahit realm. The Islamic sultanates eventually took the reins of power in the region without breaking into pieces what had already been an ancient and united domain.

Revolution as we know it today—in the context of the formation of sovereign nation-states—came at a time when many, not only the Philippines, thought of engaging the ailing colonial powers. Revolution of this kind is a fairly modern idea, which has much to do with the French Revolution. The old North Borneo, as far as I know, staged no such rebellion against Sulu. Why would it even think of raising its fists when majority of the population were also inhabitants of the Sulu archipelago? Unless, of course, proof of another story exists such as the Sultanate of Sulu maltreating its subjects. But there is no extant document to prove such a thing actually transpired.

As the battle for hearts and minds rages, it appears now that a bigger one in Malaysia is taking place, larger than the Lahad Datu incident. Election in Malaysia is right up the bend, and based on the Malaysian paper, The Edge, American newspapers have of late been allegedly hammering propaganda material to undermine opposition leader Datuk Sari Anwar Ibrahim. PKR vice-president Tian Chua said it is the mark of an insecure government to conduct such a shameful campaign, adding that he expects more from the lobby of the Malaysian government as the elections eases closer.

The report which quoted the US Department of Justice has tagged the Huffington Post, San Francisco Examiner, Washington Times and National Review as those publications singing a discordant tune about Anwar. Joshua Trevino, a said pundit, allegedly received about US$389,000 as retainers from the Malaysian government, having also paid smaller writers amounts to conduct a series of campaigns naming Anwar as “enemy of the state”.

I mentioned this particular incident as an example of how the Malaysian government conducts its affairs of state. The initial confusion as to what had happened in Lahad Datu was proof of Malaysia’s standoffish attitude towards the truth. Word that media practitioners were held back by Malaysian military forces allegedly at gunpoint spread even as the armed engagement between them and the Tausugs commenced. Why the Philippine government trusted Malaysian authorities to broker the peace between the Moro Islamic Liberation Front and the GRP Panel is a thing worth looking into. The Department of Justice, no matter how loyal its leadership is to President Aquino, must spearhead this investigation.

As of this writing, a bombing raid had commenced in the town of Lahad Datu where a few Tausugs were holed up. Reports said that Malaysia swooped down on the beleaguered Sulu warriors with everything from guns, jet fighters to tanks. With Filipino journalists pushed back, the only news that served the basis of what was happening was Malaysian news bureaus. The initial reports came in, saying that the Filipino fighters were decimated, the town levelled to the ground. It was almost as heartbreaking as it sounds, until independent Malaysian media said that despite the overwhelming onslaught, the Sulu warriors held their ground. The Malaysian air raid missed their target.

War is never anything but a sad and costly affair. A total of 26 lives have been lost since Day One of this battle, and no amount of justification can stand in the face of lives lost. Except one: honor. See, we are here dealing with a people whose ancient souls have yet to relinquish their warrior status, their thoughts of empire. Centuries of battles and centuries of ruse and subterfuge had forced the Tausugs to protect the last vestiges of royal pride and human dignity.. If President Aquino had only seen it in this light, then maybe he could’ve formulated an answer to the lingering question of Sabah and the Sultanate of Sulu. Sadly, he did not.

No, this is not simply a battle fought for land or historic claims. This is empire summoning its last ounce of courage to survive in a world that turns evermore indifferent to its way of life. In this contest, only one shall stand while the other reaps the whirlwind. Alas, this is the past and the present locked in mortal combat.